London Museum - Barbican - Aldersgate and Moorgate - The Bank and surrounding area - Cornhill - Bishopsgate - Aldgate - London Bridge and Riverside

LONDON WALL

FENCHURCH STREET, TOWER BRIDGE

UNDERGROUND: BARBICAN

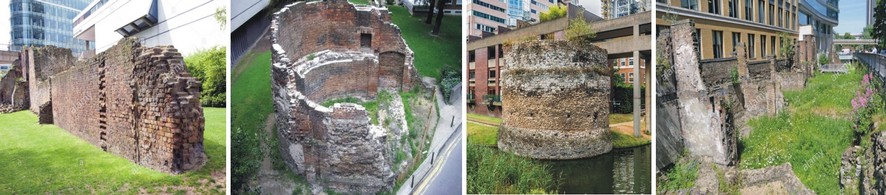

The Roman defence wall around London once went from what is currently Blackfriars, all the way to the Tower of London. During the Middle Ages it still existed and outlined the borders of the City. It was roughly three and a half kilometres long and five kilometres high, and built in bricks and coarse slate, transported over from Kent via the river, meaning hundreds of journeys back and forth. Along the external perimeter there was a moat. The gates were located in connection with the most important pathways of communication, and their names are still used today to indicate the area or the streets where they were once to be found: Ludgate, Newgate, Cripplegate, Bishopsgate and Aldgate.

The most consistent parts of the wall to have survived are near the London Museum, namely in Cooper's Row and within the Barbican Estate, where one can also observe the corner bastion of an ancient Roman fort - the time span ranging from its construction to the present day estate is just one hundred years short of two whole millennia! Another area where the walls are still intact is around Tower hill, in fact one of the largest parts of the wall is just next to the entry to Tower Hill underground station, where one may also admire a copy of the statue of Emperor Trajan.

London Wall has also lent its name to the important street which leaves Aldersgate Street, leads south of Finsbury Circus and arrives at Bishopsgate.

St Albans Tower - In Wood Street, the street which cuts across London Wall, amidst a number of extremely modern buildings, stands the tower of St Albans, with its medieval appearance. The adjoining building was completed by Wren in 1685, although the foundations were in fact much more ancient, as indicated by the fact that it was dedicated to the country's first martyr. In 1940 the bombs damaged it severely, and it was never rebuilt. Only the four-storey tower has been preserved, along with its parapet and pinnacles, which serves as a landmark..

LONDON MUSEUM

NEAR BARBICAN CENTRE

UNDERGROUND: BARBICAN

The museum is hosted within a modern building just in front of the remains of the Wall of London, and it is quite rich with relics. The exhibited galleries are arranged into two levels and these objects reconstruct the chronology of the city. As well as archaeological finds, there are dioramas which give one the illusion of being in the wake of a true panoramic view, with all its light variations. Also the artistic reconstructions, the artefacts, and the sounds in playback are of great aid for reconstructing, in one's mind, what the environment must have been like in the days of the first Britons, when hunting was the main means of survival and forests would be levelled in order to cultivate the land. Here, one can observe some copies of flint and copper axes used to such ends, and the latter may also be touched. Even everyday life in the days of the Ancient Romans has been reconstructed, depicting laboratories and artisan shops selling glasswork, leather, and knives. The background sounds replicate those of the lifestyle of way back in those days.

The museum is hosted within a modern building just in front of the remains of the Wall of London, and it is quite rich with relics. The exhibited galleries are arranged into two levels and these objects reconstruct the chronology of the city. As well as archaeological finds, there are dioramas which give one the illusion of being in the wake of a true panoramic view, with all its light variations. Also the artistic reconstructions, the artefacts, and the sounds in playback are of great aid for reconstructing, in one's mind, what the environment must have been like in the days of the first Britons, when hunting was the main means of survival and forests would be levelled in order to cultivate the land. Here, one can observe some copies of flint and copper axes used to such ends, and the latter may also be touched. Even everyday life in the days of the Ancient Romans has been reconstructed, depicting laboratories and artisan shops selling glasswork, leather, and knives. The background sounds replicate those of the lifestyle of way back in those days. As far as the medieval period is concerned, the blooming of commerce has been represented, but we can also witness the Black Death outbreak which the town fell victim to.

More real than real - The Great Fire of 1666 is represented in the diorama, with all its special effects, sounds and lights that really draw one into the dramatic sensation of that moment. We also see the building of boats and steam engines, and scientific tools... Little by little, through the centuries, we are led to the bizarre barber shop of the Nineteenth Century, with its services, shampoo, and a prepared ointment for dry-washing hair. The drug store also dates back to the same period; here, metallic boxes and painted and glazed jars contained tea and paraffin used for lighting and heating. Two thousand years' history is all wrapped up in a single spot.

At the eastern end of London Wall Street, stand the ruins of St Alphege, partially visible and incorporated into the modern adjoining buildings.

BARBICAN

SILK STREET

UNDERGROUND: BARBICAN

The Barbican complex is formed by three large blocks, located between the underground station which goes by the same name, and that of Moorgate, and has existed for about thirty years. This area had been heavily bombarded during the last war. The style of the cement buildings, which are the work of Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, are what is defined as brutalism, and have various entries, terraces, and staggered floors, a labyrinth where one can easily get lost. One of the towers, the Shakespeare Tower, built in 1976, has twenty floors. There are many small private gardens and some islets which stand amid tiny artificial lakes.

Barbican is not merely cement, but an immense fantasy of crystal panes. The enormous towers sparkle as they climb towards the heavens, and there are some small brick cottages which bring to mind those of medieval London.

Something that often seems to elude the attention of the beholder is the delightful greenhouse, to be found at the entrance to Silk Street. The arboretum holds two thousand different species of plant life. Also birds and tropical fish dwell here. The greenhouse is used mainly for private receptions and is used by the people who work at the nearby theatre.

CHURCH OF ST GILES-WITHOUT-CRIPPLEGATE

FORE STREET

UNDERGROUND: BARBICAN, MOORGATE

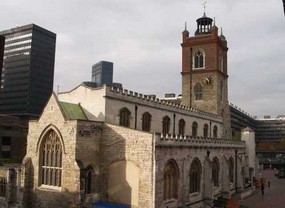

The church commemorates St Giles, protector of beggars and cripples, and is located within Barbican Centre. It is one of the few medieval churches left in the City and dates back to 1394. The present building, with a great tower standing beside the facade, is the result of the 1950 renovation, the year during which the previous building was damaged by the bombings. One of the eastern windows was designed by the Nicholson firm, where the architects, while planning it, followed the design of medieval windows. The figures of St Giles, St Bartholomew, and St Alphege are portrayed. Another pane shows the Fortune Theatre of Golden Lane. Next to it is Edward Alleyn, the benefactor of the church, and founder of the Dulwich College in 1619. On the right, we see St Luke's Church.

The church commemorates St Giles, protector of beggars and cripples, and is located within Barbican Centre. It is one of the few medieval churches left in the City and dates back to 1394. The present building, with a great tower standing beside the facade, is the result of the 1950 renovation, the year during which the previous building was damaged by the bombings. One of the eastern windows was designed by the Nicholson firm, where the architects, while planning it, followed the design of medieval windows. The figures of St Giles, St Bartholomew, and St Alphege are portrayed. Another pane shows the Fortune Theatre of Golden Lane. Next to it is Edward Alleyn, the benefactor of the church, and founder of the Dulwich College in 1619. On the right, we see St Luke's Church.BARBICAN ARTS CENTRE

SILK STREET

UNDERGROUND: BARBICAN, MOORGATE

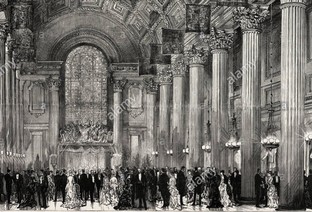

From outdoors, the cement blocks of the Barbican Centre seem cold and unpleasant, yet once inside, the foyers, the rooms, and halls are attractive and have a warm feeling about them. The acoustics of the concert room are not amongst the best, but thanks to a significant investment, it has been improved for reverb control and sound absorption, fulfilled via the use of acoustic panels.

From outdoors, the cement blocks of the Barbican Centre seem cold and unpleasant, yet once inside, the foyers, the rooms, and halls are attractive and have a warm feeling about them. The acoustics of the concert room are not amongst the best, but thanks to a significant investment, it has been improved for reverb control and sound absorption, fulfilled via the use of acoustic panels. Today the structure hosts concerts of classical and contemporary music. There are also plays, art exhibitions, and films from all over the world. There is a library and there are also three restaurants. One can dine in one of the latter and then head off to enjoy one of the shows... London has much to offer!

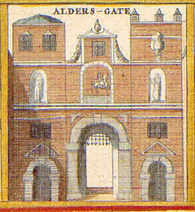

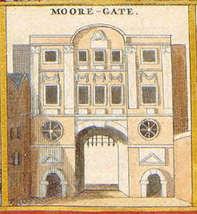

Originally, Aldersgate was a gate within the City's walls. In Aldersgate, in front of St Botolph's church, where the pastor Jon Wesley, founder of Methodism, reconfirmed his faith, there is an interesting monument commemorating such event. It consists of an iron sheet with rolled-up corners, much like an old scroll, embedded into the ground, and upon which some words have been engraved. Also Moorgate was a gate in the old Roman walls, and was demolished in 1762. Today the road that bears this name connects the City with the Islington and Hackney districts.

Originally, Aldersgate was a gate within the City's walls. In Aldersgate, in front of St Botolph's church, where the pastor Jon Wesley, founder of Methodism, reconfirmed his faith, there is an interesting monument commemorating such event. It consists of an iron sheet with rolled-up corners, much like an old scroll, embedded into the ground, and upon which some words have been engraved. Also Moorgate was a gate in the old Roman walls, and was demolished in 1762. Today the road that bears this name connects the City with the Islington and Hackney districts.  The section which lies after the City, Finsbury Pavement, was once called Moor Fields and the name Moorgate derives from it.

The section which lies after the City, Finsbury Pavement, was once called Moor Fields and the name Moorgate derives from it. In fact the area was once a moorland where laundresses would hang their laundry; this is where Londoners sought refuge during the night of the Great Fire, bringing what little they had managed to salvage of their belongings. Today Moorgate is a financial district, the headquarters of banks as well as historical buildings.

ALL HALLOWS-ON-THE-WALL

LONDON WALL

UNDERGROUND: MOORGATE

Today All Hallows belongs to the guilds and until 1994 was also the headquarters for the Council for the care of churches. The medieval building, famous for an anchorite of the Sixteenth Century, was damaged heavily by fire, and in 1765 the parishioners assigned its reconstruction to the young architect George Dance. Money was scarce and the buildable area was small, so the church, built in bricks, ended up having a very simple structure. The square tower on the western corner culminates with a dome. There is a single nave lit by three large windows, and the vaulted ceiling is decorated with white and golden coffers, and has delicate motifs. The capitals of the ionic ribbed pillars are placed directly beneath the frieze which runs all around, and the coffer ceiling of the apse is coloured blue and golden. The pulpit is accessible only via the sacristy. In the west gallery there is a small organ. The painting by Nathaniel Dance-Holland is a copy of the Anania restoring the sight of St. Paul by Pietro da Cortona. In the cemetery one can admire the ancient wall art.

Today All Hallows belongs to the guilds and until 1994 was also the headquarters for the Council for the care of churches. The medieval building, famous for an anchorite of the Sixteenth Century, was damaged heavily by fire, and in 1765 the parishioners assigned its reconstruction to the young architect George Dance. Money was scarce and the buildable area was small, so the church, built in bricks, ended up having a very simple structure. The square tower on the western corner culminates with a dome. There is a single nave lit by three large windows, and the vaulted ceiling is decorated with white and golden coffers, and has delicate motifs. The capitals of the ionic ribbed pillars are placed directly beneath the frieze which runs all around, and the coffer ceiling of the apse is coloured blue and golden. The pulpit is accessible only via the sacristy. In the west gallery there is a small organ. The painting by Nathaniel Dance-Holland is a copy of the Anania restoring the sight of St. Paul by Pietro da Cortona. In the cemetery one can admire the ancient wall art.LIVERPOOL STREET STATION

LIVERPOOL STREET, BISHOPSGATE

UNDERGROUND: LIVERPOOL STREET

Liverpool Street Station was built in 1874, following the design of E. Wilson, although the railway line that started from there had been working for more than thirty years. It was built on the Bedlam Hospital area. During World War II it was destroyed by the bombings, which caused one hundred and sixty two deaths. A funeral monument within commemorates them. In 1964 the building was once again destroyed, this time by a fire.

Very near the station, at street number 230, Bishopsgate, stands the Bishopsgate Institute, designed in 1894 by Harrison Townsend. It is a building in the Arts and Crafts style, with a huge arched entrance, windows with mullions, two polygonal turrets at the corners, which bring to mind those of fairy tale castles, and there are also sculpted decorations. It also hosts a library for consultation and a remarkable collection of printed material and illustrations, which portray glimpses of a London which has now disappeared.

PLAYING HOCKEY WITH A BROOM

12 EXCHANGE SQUARE

UNDERGROUND: LIVERPOOL STREET

The skating ring in Broadgate Circus is spartan and essential, with clay staircases. Also the surrounding buildings, which host offices, are not at all luxurious. One may come to skate all through the week, however on Monday and Thursday evening there is a peculiar event: one can play broomball, a unique version of hockey. One uses a wooden or aluminium stick, which has a rubber head at the end. The shape of this gear, shaped like a broom, is what gives the game its name. One does not use ice skates but players slide over the ice using specific shoes with special soles, made in soft rubber. Strange as it may seem, the soles are actually anti-slip, otherwise it would be difficult to brake and halt suddenly when needed during the game. Even if one does not feel up to joining in with the game, it is still most enjoyable to watch the two teams compete.

The skating ring in Broadgate Circus is spartan and essential, with clay staircases. Also the surrounding buildings, which host offices, are not at all luxurious. One may come to skate all through the week, however on Monday and Thursday evening there is a peculiar event: one can play broomball, a unique version of hockey. One uses a wooden or aluminium stick, which has a rubber head at the end. The shape of this gear, shaped like a broom, is what gives the game its name. One does not use ice skates but players slide over the ice using specific shoes with special soles, made in soft rubber. Strange as it may seem, the soles are actually anti-slip, otherwise it would be difficult to brake and halt suddenly when needed during the game. Even if one does not feel up to joining in with the game, it is still most enjoyable to watch the two teams compete. CHURCH OF ST BOTOLPH

BISHOPSGATE

UNDERGROUND: LIVERPOOL STREET

The abbot Botolph, founder of a monastery in Boston, Lincolnshire, was famous for taking care of wayfarers in particular. Because of this, near the five gates of access to the city, there were churches dedicated to him. Those of Cripplegate and Billingsgate no longer exist, however Aldgate, Aldersgate and Bishopsgate continue to survive. St Botolph's church was mentioned for the first time in 1213 and managed to endure the Great Fire, but eventually ended up in ruins. It was rebuilt in 1729 by James Gould and George Dance.

It is a large church with a brick facade, original stone decorations, and a looming tower with a circular balustrade, and a dome and urn at the top. At the sides of the entrance there are two Dorian pillars which hold up the pediment.

The old church cemetery forms a peaceful green area, and includes a fountain and a tennis court. Directly behind the church, there is a small building from 1861 where there was once a school, as indicated by the two tiny statues built in Coade stone, placed in the recesses and portraying a male and female scholar.

BUNHILL FIELDS

BUNHILL ROW

UNDERGROUND: OLD STREET

The area of Bunhill Fields overlooks a cross street of City Road and its monument ruins and gigantic plane trees give it a gothic feeling. Bunhill Fields is not a church graveyard, it is the burial place of dissenting nonconformists. In 1827 William Blake was buried here, and his tomb is often decorated with pebbles and flowers, and in 1731, Daniel Defoe as well. Also among these ranks is Eleanor Coade, owner and founder, in 1769, of the factory which produced this homonymous stone, which was used to fabricate statues, such as that of a lion on Westminster Bridge.

In 1708, the Calvinists of French origin, nicknamed Camisards, gathered here to await the resurrection of their leader, Dr. Emms, who had passed away five months earlier. Unfortunately, they were disappointed when he failed to come back to life.

One can enjoy picnics on the central lawn listening to the birds' songs, or head over to the vegetarian restaurant Carnevale, which stands on Whitecross Street, for a meal or to buy some of their delicacies to take away. It is a marvellous way to conclude the walk.

LUNARDI'S HYDROGEN BALLOON

MOORFIELDS

UNDERGROUND: MOORGATE

In 1796, from the land of the Artillery Fields, in the Moorfìelds, Lunardi's hydrogen balloon took flight, and was to provide passengers with the chance of a magnificent view over London. Vincenzo Lunardi had made his first ascension on 15th September 1784, along with a dog, a cat, and a pigeon, and had travelled for twenty-four miles.

From that moment, he had become the hero of the day, and his balloon-shaped hat and shirts decorated with drawings of hydrogen balloons were most popular. Lunardi had also successfully launched the first hydrogen balloon in England.

Today this area has been built up with skyscrapers and council housing.

THE HOUSE WHERE THE POET KEATS GREW UP

85 MOORGATE

UNDERGROUND: MOORGATE

The name on the old pub sign proclaims “Keats at the Globe”. This is in fact the very place where the romantic poet John Keats was born, in 1795. His father was a stable hand in the Swan and Hoop inn, at 199, Moorgate, at Finsbury Pavement. This type of job was a family tradition, given that his grandfather had worked in an inn. The poet, born on 31st October 1795, was baptised in the nearby church of St Botolph of Bishopsgate.

The only thing that the pub preserves of the Nineteenth Century is the name. On the inside, it is a modern setting, with pool tables and karaoke events. It serves a variety of beer, wine and liquors. There is also a large widescreen television. Near Keats' native home, at the corner of Moorgate with London Wall, stands Moorhouse, an oval building with darkened windows, which looks like the keel of a ship. It was constructed in 2005, following the design by Foster.

THE BANK OF ENGLAND

THREADNEEDLE

UNDERGROUND: BANK

The crossroads in front of the Bank of England is the meeting point of eight important streets, amongst which Threadneedle, Comhill, Lombard Street, Queen Victoria Street and Poultry. They are coasted by the offices of finance, trade, and authorities.

The Bank of England was opened in 1694 and came into state ownership in 1946, becoming the central bank of the United Kingdom. Since then, the building has been expanded twice, by Taylor and by Soane, although some parts of the previous structure have been kept. During its construction, two Roman mosaic floors were discovered, which can be seen at the foot of the main stairs. The central part of yet another item of flooring is now at the British Museum. The present building, by Herbert Baker, dates back to 1924, and has a very sober style to it. In the recesses of the facade on Threadneedle Street are two large sculptures by Charles Wheeler.

THE BANK OF ENGLAND MUSEUM

BARTHOLOMEW LANE

UNDERGROUND: BANK

In today's world we are so used to the idea of having paper money, that we rarely stop to think about what it was like in the days when it did not exist, or when it was solely a possession for the rich. In 1600, for example, the annual wage of a citizen of London was less than twenty pounds, and the smallest note was of fifty pounds, so there was a slim chance that said citizen would ever get a chance to see one, let alone actually own one.

The bank was born with the task of gathering funds for the costly military campaigns of William III against the French. The loans were made in exchange for redeemable gold deposits. Today, it is the second oldest central bank in the world, after the Swedish bank. The massive building by George Sampson, with a Palladian-style facade, has been embellishing Threadneedle Street since 1734. The museum recounts the story of the bank.

On one bulletin board, for example, there is a master book with the first sum ever to be deposited, followed by those of important characters, such as William III or Queen Mary. Another board is dedicated to old one pound notes, which were partly handwritten, much like today's cheques.  In the museum, one can also observe some tools for forgery, which appeared almost as soon as banknotes themselves. The penalty for forgery was death, but unfortunately many innocents also ended up on the gallows, having unknowingly used false money. One of the plaques explains that putting false notes into circulation was a strategy followed by Germany during the last world war with the aim of destabilizing the pound. Up until the post-war period, the bank would print only five pound notes, whereas the greater values were introduced only later, between 1964 and 1981. In one of the rooms, there are press machines from the Eighteenth Century, as well as a copy of the charter, along with videos which explain the history of the institution.

In the museum, one can also observe some tools for forgery, which appeared almost as soon as banknotes themselves. The penalty for forgery was death, but unfortunately many innocents also ended up on the gallows, having unknowingly used false money. One of the plaques explains that putting false notes into circulation was a strategy followed by Germany during the last world war with the aim of destabilizing the pound. Up until the post-war period, the bank would print only five pound notes, whereas the greater values were introduced only later, between 1964 and 1981. In one of the rooms, there are press machines from the Eighteenth Century, as well as a copy of the charter, along with videos which explain the history of the institution.

In the museum, one can also observe some tools for forgery, which appeared almost as soon as banknotes themselves. The penalty for forgery was death, but unfortunately many innocents also ended up on the gallows, having unknowingly used false money. One of the plaques explains that putting false notes into circulation was a strategy followed by Germany during the last world war with the aim of destabilizing the pound. Up until the post-war period, the bank would print only five pound notes, whereas the greater values were introduced only later, between 1964 and 1981. In one of the rooms, there are press machines from the Eighteenth Century, as well as a copy of the charter, along with videos which explain the history of the institution.

In the museum, one can also observe some tools for forgery, which appeared almost as soon as banknotes themselves. The penalty for forgery was death, but unfortunately many innocents also ended up on the gallows, having unknowingly used false money. One of the plaques explains that putting false notes into circulation was a strategy followed by Germany during the last world war with the aim of destabilizing the pound. Up until the post-war period, the bank would print only five pound notes, whereas the greater values were introduced only later, between 1964 and 1981. In one of the rooms, there are press machines from the Eighteenth Century, as well as a copy of the charter, along with videos which explain the history of the institution.CHURCH OF ST MARGARET LOTHBURY

LOTHBURY

UNDERGROUND: BANK

The church, almost hidden behind the Bank of England, was rebuilt by Wren in 1692, after the Great War. It is one of his most important churches, and in designing it, the architect decided to preserve the layout of the medieval church. The outer appearance is traditional, with a white Portland stone facade, a nice entrance porch with Corinthian pillars and a square tower of four floors, culminating in a pointed steeple, which was added later. The classical-style indoor area, is remarkable for its furniture, some of which comes from other churches of the City which were demolished.

The barrier which divides the nave from the anterior part of the church has a spectacular carving and the vast entrance arch bears an eagle with spread wings. Upon the reredos of a lateral nave, which has been transformed into a chapel, there are paintings of Moses and Aaron. The pulpit is sculpted with flowers and fruit, and surmounted by cherubs and small birds. The baptismal font is also decorated with cherubs, as well as a bas-relief of Adam and Eve, Noah's Ark, and the Baptism of Jesus. The Nineteenth Century organ is one of the most beautiful in the entire country. The walls and flooring are full of commemorative monuments. A baroque festival is also held here.

The Draper Company building - In Throgmorton Avenue, very near the church, stands the beautiful Draper Company building, and the guild has existed since 1180. At first, it included small wool merchants, then, with the passing of centuries, it became much more powerful. Today it is a philanthropic institution caring for those in need, and for educational aid. The structure preserves the brickwork of the XVII Century. At the entrance sides, there are two bearded male figures portrayed, which serve functionally as architectural support. In what was once a garden where Macaulay would stroll, today there is a building. Also in the same area, in 1253, the Austin Friars, or in other words the Augustinian monks, had built a monastery, and today there is a street here which bears their name. The ancient church had survived the Great Fire, only to be destroyed by the bombing. The new church, designed by Arthur Bailey, dates back to 1954. Beneath the altar lies an ancient stone, which was the liturgical table upon which the monks would celebrate mass.

ROYAL EXCHANGE

THREADNEEDLE STREET AND CORNHILL

UNDERGROUND: BANK The current building, located at the corner with Cornhill, is the third of those built starting from 1570, the year in which Thomas Gresham decided that the merchants needed a headquarters. The original building, swallowed up by the Great Fire, used to stand in front of a square. It had a warehouse with supplies for hundreds of shops. Also the second building, built in 1838, was obliterated by fire, and only the original turquoise flooring remains. The present building dates back to 1845 and has a vast entrance hall and a shop gallery. One can witness businessmen eating their lunch at the tables, next to the windows which overlook the courtyard.

The current building, located at the corner with Cornhill, is the third of those built starting from 1570, the year in which Thomas Gresham decided that the merchants needed a headquarters. The original building, swallowed up by the Great Fire, used to stand in front of a square. It had a warehouse with supplies for hundreds of shops. Also the second building, built in 1838, was obliterated by fire, and only the original turquoise flooring remains. The present building dates back to 1845 and has a vast entrance hall and a shop gallery. One can witness businessmen eating their lunch at the tables, next to the windows which overlook the courtyard. Behind them are a series of large paintings which portray members of the royal family, nobles, members of the clergy, and common citizens, as shown in the act of stipulating contracts and making deals. The intention of these paintings is to remind us of the financial power of the City. Also the courtyard walls were once decorated with enormous paintings, however they are now covered by the structures of temporary buildings. In front of the entrance there is a statue of Wellington, and in the courtyard there is a statue of a mother with two children. The Royal Exchange weather vane depicts a golden grasshopper, considered the symbol of trade, and an amulet which is supposed to offer protection against evil and adversity.

At number 30, Threadneedle Street, stands the Merchant Taylors' Hall. The building has been here since 1347 and has preserved many parts of the medieval walls. The crypt of a fourteenth-century chapel has also survived. The walls of the great hall are covered with a hand-painted Chinese tapestry, which dates back to the beginning of the Nineteenth Century. There is also an admirable portrait of Henry VIII.

In this building, as in those of the other guilds, churches, gardens, and squares in the Square Mile, the City of London Festival is held from the end of June to the beginning of July. The concerts are free and the list of shows includes plays, dance shows, jazz concerts, and visual art events. There are artists and musicians from far away countries.Cornhill is one of the oldest names in the City. There are two churches here, St Michael's and St Peter's, which are just as old as the former, at least when considering the initial construction. The first of the two is found in Michael's Alley and the original building precedes the Norman conquest. It is said that it was Wren who rebuilt the church in 1677, but it is more likely that it was Hawksmoor, his pupil, who drew the design and supervised the works, because Wren was by then elderly. The old tower was replaced around forty years later. The new one was gigantic and enhanced with pinnacles and sculpted heads, placed at around three quarters of the tower's height. By halfway through the Nineteenth Century, Gilbert Scott had greatly altered the church, adding a gothic porch and venetian fretwork to the windows. Later on, glasswork by Clayton and Bell was added and a new reredos was added.

Yet the most remarkable item in the church is still the organ, along with the bells.

St Peter stands at the corner of Cornhill with Gracechurch Street. Apparently, it is the oldest church in London, founded by Lucius, the first Christian king of Britannia in 179 A.D. The current building was built in 1681, as the previous one was destroyed in the Great Fire. The design is by Wren, and his daughter designed the transenna of the choir. The building is a hybrid construction, with a dome at the top of the tower, upon which there is a steeple, and above this St Peter's keys, three meters tall, shaped like a weather vane. The most noteworthy aspect of the interior is the barrier between the nave and the choir. On the reredos, a sheep's fleece has been sculpted, and represents Christ, and bears God's name engraved in Hebrew. The gallery and the organ box still preserve the original woodwork. There is also a monument dating back to 1782, dedicated to the seven Woodmason brothers; these children were burnt alive while the parents were out at a dance at St James Palace. The monument, which bears the seven heads of cherubs, was the work of the Florentine Francesco Bartolozzi. one of the greatest pressmen in Europe, who drew his inspiration from the style of the Italian masters of old.

Here, the theatre group The Players of St Peter would gather, and every year they would perform the mystery plays. The little terracotta devils seen on the north side were ordered by a vicar, in order to remind everyone about his victory upon the builders of an adjacent building, who had dared to use half a meter of land belonging to the church.

On the organ, the score of the Passacaglia by Bach is exhibited, with an autograph by Felix Mendelssohn dated 30th September 1840, and dedicated to Miss Elizabeth Mounsey, the church's organ player. Mendelssohn had played this piece on this very organ, along with Bach's Prelude and fugue.

On the southern side of Cornhill, there is a network of alleys and narrow passages, among which Ball Court, where it is most pleasant to take a walk.  In the splendid building of the Counting House, at the address of 50, Cornhill, where the Nat West Bank headquarters are located, there is now a restaurant, which still preserves elements of its financial past. The bar counter was once the bank desk, and the pretty mirror-laden ceiling is the original too. The sculpted wooden elements, the marble decorations, and the sparkling brass, are all worth a visit. At the back are some small rooms and there are tables also on the mezzanine floor. Here, one may taste the wonders of traditional and classic dishes.

In the splendid building of the Counting House, at the address of 50, Cornhill, where the Nat West Bank headquarters are located, there is now a restaurant, which still preserves elements of its financial past. The bar counter was once the bank desk, and the pretty mirror-laden ceiling is the original too. The sculpted wooden elements, the marble decorations, and the sparkling brass, are all worth a visit. At the back are some small rooms and there are tables also on the mezzanine floor. Here, one may taste the wonders of traditional and classic dishes.

In the splendid building of the Counting House, at the address of 50, Cornhill, where the Nat West Bank headquarters are located, there is now a restaurant, which still preserves elements of its financial past. The bar counter was once the bank desk, and the pretty mirror-laden ceiling is the original too. The sculpted wooden elements, the marble decorations, and the sparkling brass, are all worth a visit. At the back are some small rooms and there are tables also on the mezzanine floor. Here, one may taste the wonders of traditional and classic dishes.

In the splendid building of the Counting House, at the address of 50, Cornhill, where the Nat West Bank headquarters are located, there is now a restaurant, which still preserves elements of its financial past. The bar counter was once the bank desk, and the pretty mirror-laden ceiling is the original too. The sculpted wooden elements, the marble decorations, and the sparkling brass, are all worth a visit. At the back are some small rooms and there are tables also on the mezzanine floor. Here, one may taste the wonders of traditional and classic dishes. THE CIRCLE LINE FANS

KING WILLIAM STREET

UNDERGROUND: BANK

Nowadays we hide telephone repeaters; in the past they would cover up the fans in the underground. They were often camouflaged by a series of low, square pillars, covered in bas-reliefs, with a roof-like element jutting out at the top. At the foot of a statue in King William Street, there is a net protecting an underlying fan belonging to the Circle Line. The statue is of James Greathead, the inventor of the tunneling shield which facilitated the opening of the galleries in the London underground area for the construction of the tube. Greathead is depicted with a wide-brimmed hat, as he distractedly looks at a map and holds his jacket under his arm. The statue was erected in 1994 and sculpted by James Butler and later relocated to King William Street, which is the northbound progression of London Bridge.

LOMBARD STREET

UNDERGROUND: BANK, MONUMENT

Lombard Street is the road that goes from the corner of the Bank of England up to a point where it crosses paths with Poultry Street, King William Street and Threadneedle Street. Already in the Middle Ages, this was an area of concentration for the main activities connected to money management. The street gets its name from the Italian bankers who dwelled there in the Fourteenth Century and were mainly from Lombardy. European monarchs would entrust them with their money. In those days, banks used to bear insignia with symbols, Lloyd’s sported a horse, the bank of Alexander an artichoke, the Coutts three crowns, the Martin a grasshopper, and the William & Glyn’s bore an anchor.

Lombard Street is the road that goes from the corner of the Bank of England up to a point where it crosses paths with Poultry Street, King William Street and Threadneedle Street. Already in the Middle Ages, this was an area of concentration for the main activities connected to money management. The street gets its name from the Italian bankers who dwelled there in the Fourteenth Century and were mainly from Lombardy. European monarchs would entrust them with their money. In those days, banks used to bear insignia with symbols, Lloyd’s sported a horse, the bank of Alexander an artichoke, the Coutts three crowns, the Martin a grasshopper, and the William & Glyn’s bore an anchor.The name of the street entered into idiomatic English with the old idiom: “Lombard Street to a China orange", meaning very heavily-weighted odds.

Until 1980, the street was the headquarters of many British banks, including Lloyd’s. Yet Lombard Street is not only the road of banks, but also that of churches. One of these is St Edmund’s. The church bears the name of the monarch who became a martyr at the hands of the Danish in 870 A.D. In fact his complete name is St Edmund King and Martyr.

The medieval church, where John Shute was buried, author of the first treatise on the history of architecture, was destroyed in the Great Fire. The present building dates back to 1679 and is the work of Wren. It is built in Portland stone with a square tower supporting an octagonal lantern and a steeple which is also octagonal.

The medieval church, where John Shute was buried, author of the first treatise on the history of architecture, was destroyed in the Great Fire. The present building dates back to 1679 and is the work of Wren. It is built in Portland stone with a square tower supporting an octagonal lantern and a steeple which is also octagonal. On the inside, the pillars of the balustrades of the communion have an unusual shape, the organ is divided into two parts, Moses and Aaron are painted on the reredos, the baptismal font in marble bears a decoration in acanthus wood, and a wooden cover with golden statues of the apostles.

CHURCH OF ST MARY WOOLNOTH

LOMBARD STREET

UNDERGROUND: BANK

The name Woolnoth derives perhaps from the Saxon Wulfnoth. The church at the corner of King William Street, is one of those that William the Conqueror had built in stone. In 1727, Hawksmoor rebuilt it, with the monumental facade that we see still today. T.S. Eliot wrote the following words about it in The Waste Land, I,66-68:

The name Woolnoth derives perhaps from the Saxon Wulfnoth. The church at the corner of King William Street, is one of those that William the Conqueror had built in stone. In 1727, Hawksmoor rebuilt it, with the monumental facade that we see still today. T.S. Eliot wrote the following words about it in The Waste Land, I,66-68:Flowed up the hill and down King William Street

To where Saint Mary Woolnoth kept the hours

With a dead sound on the final stroke of nine.

The facade is unusual, with a colonnade on the first floor and two truncated towerlets for the bells.

It has a square layout with three Corinthian pillars at each corner, and the flat ceiling is painted blue and strewn with golden stars.

The altar is covered by an extremely elaborate canopy, the chandelier is in remembrance of Colonel Buxton, a good friend of Lawrence of Arabia. One of the funeral monuments is dedicated to John Newton, a slave trader who later became a minister, and who preached here for quite some time. Another monument commemorates Edward Lloyd, the owner of a café which became an initial location for organizing insurance for ships, and later became a worldwide affair.

There is also a monument commemorating the inventor Henry Fourdrinier, grandfather of cardinal Newman, who was in turn founder of the Oxford Movement, which was recently beatified by pope Ratzinger. On Easter week, the service and sermon is attended by the Lord Mayor and the City authorities, who dress in ceremonial robes.

An altar of fragments – In the nearby Clement’s Lane stands the church of St Clement’s, a small building designed and built by Wren in 1687, with a brick tower in full sight. The inside, completely white, emphasizes the magnificence of the pulpit. The organ was installed at the end of the XVII Century by Renatus Harris. Henry Purcell and Jonathan Battishill were both organ players here. The altar is the work of Grinling Gibbons and is noteworthy. It was blown to bits by the bombs, but was patiently pieced together again during the early Fifties. Also the pulpit and the wooden canopy, sculpted towards the end of the Seventeenth Century, are pleasing to the eye. The bombings revealed a crypt dating back to the XIV Century.

An altar of fragments – In the nearby Clement’s Lane stands the church of St Clement’s, a small building designed and built by Wren in 1687, with a brick tower in full sight. The inside, completely white, emphasizes the magnificence of the pulpit. The organ was installed at the end of the XVII Century by Renatus Harris. Henry Purcell and Jonathan Battishill were both organ players here. The altar is the work of Grinling Gibbons and is noteworthy. It was blown to bits by the bombs, but was patiently pieced together again during the early Fifties. Also the pulpit and the wooden canopy, sculpted towards the end of the Seventeenth Century, are pleasing to the eye. The bombings revealed a crypt dating back to the XIV Century.MANSION HOUSE

WALBROOK

UNDERGROUND: MANSION HOUSE

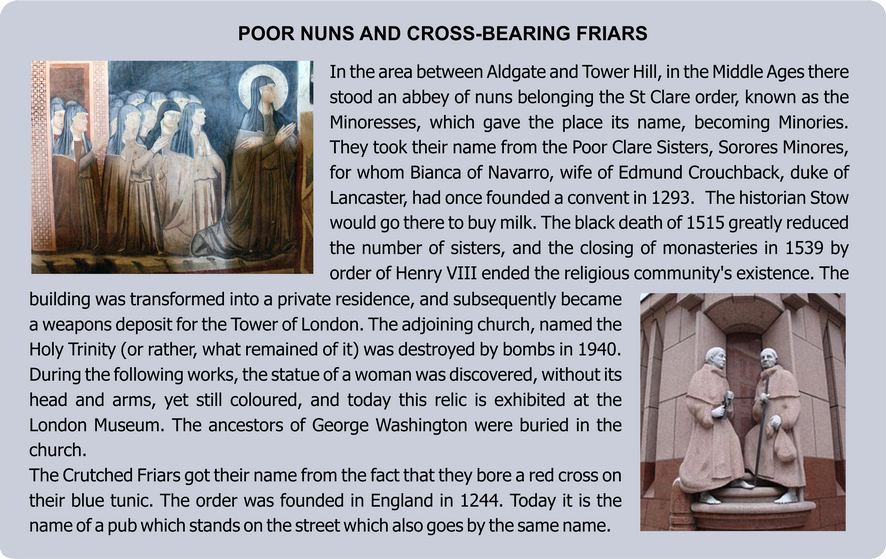

Mansion House is the official residency of the Lord Mayor of the City. The entrance is on Walbrook and the facade has an enormous elevated porch, supported by six impressive Corinthian pillars, which can be reached via a double staircase. Above the pediment stands a sculpture of Robert Taylor, which represents the opulence and sense of decorum of the City. In 1728 it was decided that a house be built for the Mayor, and the choice was made to do so upon the area of the old stock exchange building. Amongst the participants in the competition for the best project, also Giacomo Leoni was present, yet George Dance the Elder won. The building is made of Portland stone and the terrain was so marshy that the edifice had to be built upon pillars. At the first floor, there are delegation rooms and the Justice Room, seeing as the Lord Mayor is also the president of the City Court. There is a series of halls here, which are really quite magnificent, one of the most beautiful being the Venetian Parlour, with its marvellous chimneys, the carved wood and plasterwork.

Mansion House is the official residency of the Lord Mayor of the City. The entrance is on Walbrook and the facade has an enormous elevated porch, supported by six impressive Corinthian pillars, which can be reached via a double staircase. Above the pediment stands a sculpture of Robert Taylor, which represents the opulence and sense of decorum of the City. In 1728 it was decided that a house be built for the Mayor, and the choice was made to do so upon the area of the old stock exchange building. Amongst the participants in the competition for the best project, also Giacomo Leoni was present, yet George Dance the Elder won. The building is made of Portland stone and the terrain was so marshy that the edifice had to be built upon pillars. At the first floor, there are delegation rooms and the Justice Room, seeing as the Lord Mayor is also the president of the City Court. There is a series of halls here, which are really quite magnificent, one of the most beautiful being the Venetian Parlour, with its marvellous chimneys, the carved wood and plasterwork. The pharaoh’s hall – Beyond what was once the courtyard, and is now covered, was the Egyptian Hall, built following Vitruvio’s description of what he presumed to be the style of Egypt. It is however unlikely that a pharaoh would have found much familiarity in it. Upon the four walls, there are huge pillars which climb up to the ceiling, and between them and the wall, there is the space for an ambulatory. The walls are full of niches which hold statues representing characters from English literature. Amongst these, are Egeria by Foley, Griselda by Marshall, Britomart by Wyon, and Sardanapalus by Weekes.

The pharaoh’s hall – Beyond what was once the courtyard, and is now covered, was the Egyptian Hall, built following Vitruvio’s description of what he presumed to be the style of Egypt. It is however unlikely that a pharaoh would have found much familiarity in it. Upon the four walls, there are huge pillars which climb up to the ceiling, and between them and the wall, there is the space for an ambulatory. The walls are full of niches which hold statues representing characters from English literature. Amongst these, are Egeria by Foley, Griselda by Marshall, Britomart by Wyon, and Sardanapalus by Weekes. There is also a collection of gold and silver items, as well as insignias and decorations connected to the office: a crystal sceptre mounted on gold, a ceremonial chain, a mace dating back to 1735, and some swords. The ceremonial sword was fabricated in Ferrara during the reign of Charles II.

AN EXPERIMENT FOR THE CATHEDRAL

39, WALBROOK

UNDERGROUND: BANK

The church of St Stephen stands behind Mansion House, west of which a road runs, known as Walbrook. It was constructed by Wren in 1679 and in building it, the architect tried out his design for St Paul’s. In spite of the small size, it gives a feeling of vastness, also due to the dome and the effects created by the play of light. Some of the items have been crafted to a high degree of perfection, such as the pulpit, with the cherubs dancing on the canopy, the altar and balustrade, the baptismal font and its cover.

All these elements have been preserved as Wren left them. In the west gallery there is an organ installed in 1765. Once the Walbrook river used to flow in the place where today there is a street going by the same name, and it was navigable and used by the ancient Romans for reaching the temple of the God Mithras, which stood on the banks.

MITHRA'S TEMPLE

QUEEN VICTORIA STREET

UNDERGROUND: BANK

In 1954, on the banks of the Walbrook, the ruins of a temple dedicated to Mithra were discovered. Studies have revealed that the date of construction was around halfway through the III Century. Also a group of sculptures was found, which had perhaps been buried to hide them from Christian iconoclasts. Among these, were the heads of Mithras, Minerva, and Venus. There were also statuettes of Mercury and Dionysus, with a silver box bearing scenes of mysterious rituals. It was decided that the remains of the temple be erected once again near the original setting, on Queen Victoria Street. However, it is impossible to recreate the sense of the secret esoteric place that it once was.

At the London Museum one can witness the complete reconstruction, with the salvaged items and sculptures inside. One of these is a bas-relief in marble with the god Mithras depicted on it, in the act of killing the bull. Also appearing on the bas-relief, are the twins Cautes and Cautopates, assistants to Mithras, and Helios, god of the Sun, as he ascends into the sky on his chariot. On a large block of stone there are sculptures of the Moon and the gods of the winds: Boreas, the god of the cold northern wind, and Zephyr, the god of the western wind. An engraving tells us that the soldier Ulpius Silvanus had the altar built in order to fulfil a vow.

In the north-eastern arch of the City, which escaped the devastation of the Great Fire, there are numerous medieval buildings. The name Bishopsgate, which indicates a road and a neighbourhood, derives from the name of one of the seven gates which used to lead into London through the wall. The original Roman gate had been remade in 1471 by the Hansa merchants. In 1735 the City authorities rebuilt it in its final form. This is where the head of criminals were exposed, skewered onto the ends of spears. In 1760 the gate was demolished. The place is marked by a stone strewn with symbols, known as Bishop's Mitre, and placed upon a building at the crossing of Wormwood and Camomile Street with Bishopsgate. At its base, it shows the barrier made up by the City walls.

A pub filled with dust and cobwebs – At number 202, Bishopsgate, in front of Liverpool Street Station, stands a historical pub known as Dirty Dick's, which has become something of an institution in the city. On the signpost is the figure of a eighteenth-century gentleman. The pub was opened in 1745 and it is thought that its name gave Miss Haversham the inspiration for Great Expectations.

The original name of the pub was Old Jerusalem, however the owners decided to rename it after the famous warehouse on Leadenliall Street. The latter was known as Dirty Dicks because the owner, after a romantic setback which ended in disappointment, he no longer bothered to keep it clean and tidy, leaving it to gather cobwebs and dust. It seems the owner of the pub followed the same behaviour in the bar and distillery. The beautiful pub is on three floors, and beneath its cave-like arches, there are many unusual artefacts. It is famous for its fish & chips and Sunday roast.

CHURCH OF ST ETHELBURGA

78, BISHOPSGATE

UNDERGROUN: BANK, LIVERPOOL STREET

The tiny church of the City, dedicated to St Ethelburga was mentioned for the first time in a document in 1250. The walls are made up of debris and slate, and in the western wall, there is an entrance gate dating back to the Fourteenth Century and a window from the following century. The small square tower is overlooked by a bell tower from the Eighteenth Century and a weather vane from 1671.

It is one of the few medieval churches to have survived the Great Fire of London in 1666 and the bombs of the Second World War. Unfortunately, after having made a clean escape from these two disastrous events, it was almost completely destroyed by an I.R.A. bomb in 1993. The indoor area is quite bare, there is a wooden altar and there are a few paintings. The eastern wall is decorated by a wall painting, which depicts the Crucifixion, St. Luke with a patient and St Ethelburga with a group of children. Today the church hosts a Center for Reconciliation and Peace, which organizes a good deal of meetings between populations in conflict. On the terrain at the back, there is a tent, inside which are some benches and carpets which come from war zones. One may come here to meditate and pray. Some messages of peace are written in different languages on the walls.

The last communion of the explorer – On 19th April, 1607, the explorer Henry Hudson and his team received their communion in this church, the day before leaving aboard the Discovery in search of the north-western passage to China and India. Unfortunately, a tragic destiny was in store for them. In June 1611, at the mouth of the Canadian river known today as the Hudson, the crew mutinied. The explorer was abandoned to his fate on a small boat, along with his son and a handful of sailors. They were never to be found again, despite an expedition being launched to rescue them. They almost certainly died of hunger and cold. Various episodes of the unfortunate expedition are portrayed on the windows of the southern nave, carried out by Leonard Walker in 1930.

A POLYCHROME TURKISH BATH

8, CHURCHYARD

UNDERGROUN: LIVERPOOL STREET

The tiny building of the Turkish Baths is a quaint, delightful gem of architecture. It was built by Harold Elphick when London was invaded by the fashion for all things Oriental, as well as the taste for exoticism. In designing it, the architect referred to a reliquary from the Nineteenth Century, which is located in the church of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, decorated with names on the walls.

The tiny building of the Turkish Baths is a quaint, delightful gem of architecture. It was built by Harold Elphick when London was invaded by the fashion for all things Oriental, as well as the taste for exoticism. In designing it, the architect referred to a reliquary from the Nineteenth Century, which is located in the church of the Holy Sepulchre of Jerusalem, decorated with names on the walls.During the Victorian period, as well as being a hygienic habit, Turkish baths were considered a way to relax, first off in a hot environment, and subsequently in cold water. At the end of all this, there was a massage. It was a crossover between roman thermal baths and Turkish tradition. The many-coloured tiles and vivid windows are typical of the end of the Nineteenth Century. The building survived the Blitz and presently belongs to the Gallipoli restaurants.

CHURCH OF GREAT ST HELEN

LIME STREET WARD

UNDERGROUND: LIVERPOOL STREET

The church of St Helen’s, which is extremely close to the Lloyd’s Building and the Gherkin, is in remembrance of Emperor Constantine's mother, who had been mysteriously guided to retrieve the cross of Jesus. In 1631, a classical entrance was installed which is pleasing to the eye, and clearly influenced by Italian style. The baptismal font dates back to 1632. Many merchants and authorities of the City chose to be buried in this church, and for this reason it was named Westminster Abbey of the City. The church contains funeral monuments and ancient tombs. On master mason Kirwin’s tomb, there is an engraving in Latin, which states: “I have adorned London with so many noble buildings, and fate has reserved this small home for me. I have built royal palaces for others, and erected this tomb for my bones.”

The duel of Julius Caesar – In the presbytery lies Julius’ Caesar’s tomb, judge, politician, and person in charge of state archives, and was the son of Giulio Cesare Adelmare, a physicist at the service of Queen Mary I. The third wife of Julius Caesar was the niece of the philosopher Francis Bacon. The judge died in a bizarre way at the age of eighty. He had been injured whilst fencing with Antonio Brachetta and thus tried to get his revenge by shooting his opponent while hidden from sight. Unfortunately for him, he missed the target and was beaten to death by his adversary, after a failed attempt at extracting a sword. His death seems something of a contradiction when compared with the writing on his tomb, which states: “Julius Caesar is ready to pay God his debt in nature in any moment that He may decide so.” Next to the monument to the fallen, erected in 1921, there is a ladder leading to the monks’ dormitory, which allowed them to direct access to the area by night. If any of them were at all ill, they were therefore able to follow mass through an eyelet. In 1993, an I.R.A. bomb, which almost demolished the church of St Ethelburga, wrecked the ceiling and the two large Sixteenth-century windows of this church.

LEADENHALL MARKET

WHITTINGTON AVENUE

UNDERGROUND: BANK, MONUMENT

The market, which is situated in a cross street of Gracechurch Street, dates back to the XIV Century and stands on the area of a Roman basilica, where there was a forum, shops, and flooring with mosaics. One of these represents Bacchus as he rides a tiger, and is currently in the British Museum. The structure found there today, made of glass and wrought-iron, is from the Victorian age. Its name stems from the lead roof of the great hall, which was commissioned by Hugh Neville in 1881 and designed by Horace Jones, who had also designed Billingsgate and Smithfield. This market is renowned for its wild game, courtyard animals, and fish, as well as herb, spice and grocery stores. The construction of the roof, green, yellow, and brown, makes it quite scenic and ideal for visiting on a walk. It has also become a touristic attraction, thanks to the film Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s stone, which was shot in this location. Through the years, an open market has grown all around it. This is also the place where those working in nearby offices go to shop. Because of this, at lunch time it is usually quite crowded.

Leadenhall Street – The street goes from Cornhill to Aldgate and is one of the most important ones in the City. It gets its name from the metal roof of the market, which was once used as a deposit for wheat. Between it and the church of Great St Helen’s, there is a large paved square, converted into a large pedestrian area. The headquarters of the Peninsular and Oriental Steam Navigation Company, abbreviated to P&O is located here. The unusual building consists of a block of ten floors of glass and steel, and rests upon a smaller platform, which is two floors high. In the courtyard stands a gigantic statue portraying Navigation and a maypole, painted in vivid colours. At number 56, we find the London Metal Exchange, whereas at number 122, there is a skyscraper nicknamed “the grater”.

The delightful building of East India House, which was the headquarters of the Company of the Indies, used to be on this street. The Company was formed in order to encourage the trading of silk, cotton, indigo, tea, spices, and saltpetre with the Oriental Indies. Later on, it had ended up administrating and governing a large part of India, also through a use of military power. Things only changed when in 1857, what the English called the Great Mutiny took place, although by Indians this is known as the First War of Independence. From that point onwards, it was the British government which took direct control of assets, with the British Raj, the imperial phase of English domination in India.

In 1869 the building was demolished and in 1874 the Company was disbanded. Today the area is occupied by a Lloyd's Building.

At number 86 of the same street, we find the church of St Katharine Cree. Cree is a deformation of Christ. The church was founded by Matilda of Scotland, wife of Henry I, whereas the present building dates back to 1631. It is one of the churches of the City guilds, and the inside area is rectangular and very simple, with an arched roof and rose window which belong to the original choir. On one of the western windows, St Katherine of Alexandria is depicted, in the act of being tortured because of her faith. Henry Purcell and Georg Friedrich Handel once played the organ in this church. Amongst those buried here, is John Gayer, who had paid two hundred pounds in exchange for a sermon to be held each year, on 16th October, in memory of his being saved from a lion, when he was a young merchant travelling through Turkey. The sermon is still held today. Today the church is the headquarters of the Industrial Christian Fellowship.

LLOYD'S BUILDING

1, LIME STREET

UNDERGROUND: MONUMENT

Those who adore the architecture of the Paris Centre Pompidou will beam at this building built by Richard Rogers, which switches those services that would usually be situated on the inside to an outside position. Because of this, it is called the Inside-Out building. The stairs, twelve glass lifts, electrical conduits and water pipes are all in full view. The building is fourteen floors high, with a height of eighty-eight metres, and was constructed between 1978 and 1986. It is made up of three larger towers and three small ones, built around an extremely tall atrium.

The Committee Room is on the eleventh floor, in the form of an eighteenth-century dining hall designed by Robert Adam, and was part of the previous building. Also the incredibly tall cranes have been left in their place, as decorative elements. The Lloyd’s insurance company was born in 1686 in a coffee shop on Tower Street, opened by Edward Lloyd. The venue soon became the meeting place for, ship owners and commanders, and merchants interested in providing the ships’ goods. A few decades later, the classification and insurance of ships started being formally organized, and all practices were from then on registered.

THE MAYPOLE CHURCH

ST MARY AXE

UNDERGROUND: MONUMENT

The first of St Andrew’s churches was built in 1147, the current one dates back to 1530.

The Renaissance-style entrance is noteworthy, and also the door-knocker is pretty. The inside area is filled with precious items, amongst which the pulpit sculpted with fruit and flowers, the organ, and the windows bearing portraits of Edward VI, Elisabeth I, James I, Charles I, and Charles II. The baptismal fount in marble was paid for by the parishioners, who had taxed themselves to this purpose. In the north-eastern corner of the church, there is a monument commemorating the historian John Stow, who is buried here. Stow is the author of an important survey of the city, which accurately describes the buildings, the social conditions, and the ways of life during the reign of Elizabeth I. Stow, whose house was in Lime Street, lived in poverty, seeing as his job was not a well-paid one, but after his death, this pretty monument was dedicated to him, and is well-deserved.

Maypole – The church is called Undershaft because of the tall maypole which once projected its shadow on the bell tower. However, it was no longer erected after the Evil May Day riots of 1517, when the apprentices violently attacked foreigners and tore down the maypole. Henry VIII had some of them hanged and the pole was left on the ground and later cut up into pieces by the parishioners of the nearby church of St Katharine Cree.

In the days of ancient Rome, at the corner of what is now Duke’s Place, the wall contained a gate corresponding to the road for Colchester. The opening was later widened and became the easternmost gate between the City and Whitechapel. Next to it, in 1108, Queen Matilda, wife of Henry I, founded the Augustinian convent of the Holy Trinity. Here, in 1420, also the Whitechapel Bell foundry was opened.

Between 1374 and 1386, Geoffrey Chaucer, who was a customs officer, lived in the two rooms directly above the convent, and a blue plaque has been fitted in his memory.

Present-day Aldgate Street is only fifty metres long, and serves as a connection with Aldgate High Street. It hosts two buildings: the headquarters of an insurance company, and a school dedicated to John Cass. On the façade of the latter, a plaque reminds us of the fact that this is where the London Wall used to pass through.

CHURCH OF ST BOTOLPH-WITHOUT-ALDGATE

ALDGATE HIGH STREET

UNDERGROUND: ALDGATE

The church is situated at the junction between Houndsditch and Aldgate High Street. Although its foundations date back to the period prior to the Norman conquest, the first document which mentions it dates 1115. It was built just before the Reform, and in 1683 Daniel Defoe got married here. The church residing there currently dates back to 1744 and was designed by George Dance the Elder. It is built in the Georgian style, with bricks and stone corner ashlars, and a square tower above the entrance door. On the inside it is well-lit, and is home to a beautiful organ from 1704 by Renatus Harris. The octagonal vestibule has been transformed into a baptistery. The marvellous ceiling is the work of Bentley and in the arched sections, above the galleries, there are rows of exalting angels, which embody the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement. Along the walls there are niches with plaques and funeral monuments. The oldest of these is represented by a an alabaster slab with a relief of a scrawny, draping figure. It seems like it could be lord Darcy, who, along with Nicholas Carew, was beheaded on Tower Hill for having opposed the religious changes ordered by Henry VIII.

The church is situated at the junction between Houndsditch and Aldgate High Street. Although its foundations date back to the period prior to the Norman conquest, the first document which mentions it dates 1115. It was built just before the Reform, and in 1683 Daniel Defoe got married here. The church residing there currently dates back to 1744 and was designed by George Dance the Elder. It is built in the Georgian style, with bricks and stone corner ashlars, and a square tower above the entrance door. On the inside it is well-lit, and is home to a beautiful organ from 1704 by Renatus Harris. The octagonal vestibule has been transformed into a baptistery. The marvellous ceiling is the work of Bentley and in the arched sections, above the galleries, there are rows of exalting angels, which embody the spirit of the Arts and Crafts movement. Along the walls there are niches with plaques and funeral monuments. The oldest of these is represented by a an alabaster slab with a relief of a scrawny, draping figure. It seems like it could be lord Darcy, who, along with Nicholas Carew, was beheaded on Tower Hill for having opposed the religious changes ordered by Henry VIII.Yet another plaque looks like it represents William Symington, builder of the Charlotte Dundas, the first steamboat. However, the real treasure of St Botolph’s is a wooden panel from the late Eighteenth Century, which portrays King David playing a harp. The church is very near Mitre Square, which is where the murder of Catherine Eddowes took place at the hands of Jack the Ripper.

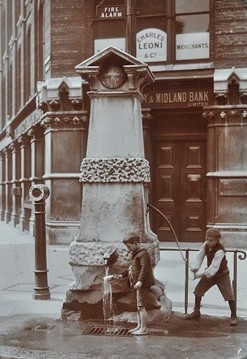

THE ALDGATE PUMP

ALDGATE HIGH STREET

UNDERGROUND: ALDGATE EAST

The Aldgate Pump stands at the junction of Aldgate Street with Leadenhall Street and Fenchurch Street, and is shaped similarly to a small obelisk. It’s history goes back as far as the Sixteenth Century, during which it was erected in place of the old well. It has always been a point of reference, a landmark for measuring distances and indicating the official point where the East End began. The pump has been declared of architectural interest. It bears a small wolf’s head, which is perhaps a reminder of the last wolf hunted down here. The historian John Stow already spoke of this in his A Survey of London in 1598. The current building, however, which stands a little to the left compared to the former one, dates back to 1876, and after all these years continues to be used. Like other water pumps in London, this one too is tied to a sad story, according to which its waters were contaminated and caused the deaths of many people. The research carried out following locals’ complaints about its strange taste revealed that this was due to calcium released by the skeletons in cemeteries through which the water passed to get to the pump. Today, to make the regulator tap work, one must first press a button, yet the old handle is still in place. In Uncommercial Traveller Dickens wrote: “My interest as an uncommercial traveller invited me that day to visit the East End, so I set off in that direction, just after having passed by the Aldgate Pump.

The Aldgate Pump stands at the junction of Aldgate Street with Leadenhall Street and Fenchurch Street, and is shaped similarly to a small obelisk. It’s history goes back as far as the Sixteenth Century, during which it was erected in place of the old well. It has always been a point of reference, a landmark for measuring distances and indicating the official point where the East End began. The pump has been declared of architectural interest. It bears a small wolf’s head, which is perhaps a reminder of the last wolf hunted down here. The historian John Stow already spoke of this in his A Survey of London in 1598. The current building, however, which stands a little to the left compared to the former one, dates back to 1876, and after all these years continues to be used. Like other water pumps in London, this one too is tied to a sad story, according to which its waters were contaminated and caused the deaths of many people. The research carried out following locals’ complaints about its strange taste revealed that this was due to calcium released by the skeletons in cemeteries through which the water passed to get to the pump. Today, to make the regulator tap work, one must first press a button, yet the old handle is still in place. In Uncommercial Traveller Dickens wrote: “My interest as an uncommercial traveller invited me that day to visit the East End, so I set off in that direction, just after having passed by the Aldgate Pump.PETTICOAT LANE MARKET

MIDDLESEX STREET

UNDERGROUND: ALDGATE

Petticoat Lane was the old name for Middlesex Street. The name was changed due to excessive prudishness, because of the fact that a petticoat was an item of underwear. It had got its name because of the fact that this was a place where clothes and second-hand underwear would be sold or bartered. The market has existed since 1608 and is one of the traditional trading places of the eastern area of town. The area has always been associated with textile products, dyed and packaged by immigrants, starting with the Huguenots. In more recent times, it has become popular among tourists. One can even find designer clothes from the previous year. In Aldgate East merchants sell leather clothing, next to the bric-à-brac stands. It is worth coming here to take a look around even without necessarily buying anything, however it is a good idea to be on the watch for pickpockets who may attempt to pinch one's wallet.

Next to Petticoat Lane market is Brushfield Street market. At the northern end of the market street, in Widegate Street and Artillery Lane, one may witness the remains of a few elegant eighteenth-century facades on the shops. The line of the City walls is marked by Houndsditch, which gets its name from the carcasses of animals which used to be thrown into it.

THE BEVIS MARKS SYNAGOGUE

2 HENEAGE LANE

UNDERGROUND: ALDGATE

The strange name of this synagogue, which stands on a street parallel to Bevis Marks, is a mangling of Bury's Marks. Before the closing of monasteries, ordered by Henry VIII, the area belonged to the abbots of Bury St Edmunds, and Marks indicated the sign of a boundary.

The synagogue, founded by sephardic Jews, dates back to 1679 and is the oldest in England. It is the only one in Europe where a religious service has been held continually for more than three hundred years. King Edward I had once expelled them, but Cromwell, who needed their capitals, allowed them to reside on English territory.

The Quaker Joseph Avis, who was also the builder of the synagogue, had not asked for payment, as he did not deem it proper to earn money from erecting a house of God. On the inside, all the chairs face the centre. The most important item is the wonderful Echal or Ark, the sacred place which is used for preserving the Torah scrolls, in Renaissance style. At the centre of the synagogue stands a raised altar-step, also known as Tehah. There are also some splendid brass candleholders. The whole environment is extremely interesting, especially as it has not undergone any changes. One area of the hall functions as a kosher restaurant.

FENCHURCH STREET STATION

FENCHURCH PLACE

UNDERGROUND: ALDGATE

Fenchurch Street station is small, with only four platforms. It was built in 1841 following William Tite's design and was the first in the City. A white ornamental protrusion stands out against a pretty grey brick wall, and consists of a motif of architectural decoration formed by ledges in coving, just like those found in quaint little country stations. Above it are eleven arched windows and a clock in the centre. The two roof slopes are rounded, and some offices have been built above the tracks.

Just north of Fenchurch Place lies Camomile Street. The street's name reminds us of the fact that once, during the Middle Ages, wild herbs used to grow here. The same goes for Wormwood Street, which is situated just opposite. "Wormwood" does not literally stand for "a wood full of worms", as one might mistakenly surmise. Instead, the name comes from the assonance with Vermouth, and indicates the aromatic plant known as Artemisia absynthium, which is used as a traditional ingredient of this particular drink, and also for distilling Absinth. Along with camomile, it is a precious therapeutic plant. The memory of the place where they once used to grow has remained in the name of the street.

Mincing Lane is the street where the clothworkers' building is situated. Its name comes from the Anglo-Saxon word mynechene, meaning "nun". The modern building, designed by H. Austen Hall in 1938 in the neo-Georgian style, hosts the Worshipful Company of Clothworkers, which has existed since 1528, the year the fullers and shearmen guilds joined as one. The exquisite Pepys Cup is part of the superb collection of silverware, and was donated by Samuel Pepys, famous for his diary writings, in 1677, when he was the president of the company.

CHURCH OF ST OLAVE

HART STREET

UNDERGROUND: FENCHUCRCH STREET

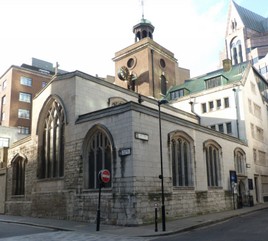

The church of St Olave, at the junction between Crutched Friars, Hart Street and Seething Lane, is one of the smallest churches in the capital, with an almost square layout. The arches date back to the Fifteenth Century, and the Eighteenth-century pulpit is richly sculpted. The warrior prince Olaf's conversion to Christianity provoked a strong reaction amongst his subjects, so much as to induce them to rebel. He fell in the battle of Sticklestad on 29th July 1030 and was proclaimed a saint one year later. The church was very dear to Samuel Pepys, who was its most illustrious parishioner because of the fact that he worked at the nearby Navy Office and lived in the neighbourhood. In his Diaries he refers to it as “our church", meaning his own and of his wife, and was more than happy to sit together with her at the pew for the naval officers. Today they are both buried there. His wife, whom he married when she was only fifteen, died at the age of twenty-nine, and was buried here thirty-four years earlier than him. Amongst the funeral monuments, there is a bust painted in vivid colours representing Peter Cappone, a gentleman from Florence who died in London in 1582. He was banished from his city and left for London, however he then fell ill to the plague outbreak. There is a tablet commemorating Dr. William Turner, who died in 1568, the creator of the first English herbarium, with the names of plants catalogued in Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian. This use of scientific botanical terms introduced England into the map of plants in Europe. Prior to this, only the common names were used to identify them.

The church of St Olave, at the junction between Crutched Friars, Hart Street and Seething Lane, is one of the smallest churches in the capital, with an almost square layout. The arches date back to the Fifteenth Century, and the Eighteenth-century pulpit is richly sculpted. The warrior prince Olaf's conversion to Christianity provoked a strong reaction amongst his subjects, so much as to induce them to rebel. He fell in the battle of Sticklestad on 29th July 1030 and was proclaimed a saint one year later. The church was very dear to Samuel Pepys, who was its most illustrious parishioner because of the fact that he worked at the nearby Navy Office and lived in the neighbourhood. In his Diaries he refers to it as “our church", meaning his own and of his wife, and was more than happy to sit together with her at the pew for the naval officers. Today they are both buried there. His wife, whom he married when she was only fifteen, died at the age of twenty-nine, and was buried here thirty-four years earlier than him. Amongst the funeral monuments, there is a bust painted in vivid colours representing Peter Cappone, a gentleman from Florence who died in London in 1582. He was banished from his city and left for London, however he then fell ill to the plague outbreak. There is a tablet commemorating Dr. William Turner, who died in 1568, the creator of the first English herbarium, with the names of plants catalogued in Greek, Latin, French, German, and Italian. This use of scientific botanical terms introduced England into the map of plants in Europe. Prior to this, only the common names were used to identify them.Another of Turner's merits, according to the writing on the table, is that of having fought "against the enemies of the Church and the Commonwealth, chiefly the Roman Antichrist".

Sniggering skulls - The arched entry to the church, on Seething Lane, is surmounted by sneering stone frescos and crossed shinbones placed there in 1658, with a phrase in Latin: "Mors mihi lucrum ("death is my fortune"). Dickens was particularly moved by this and spoke of it in Uncommercial traveller. Because of the three skulls which loom over anyone who dares to enter, the writer had nicknamed this city of the dead "the cemetery of St Ghastly Grim". It is rumoured that Mary Ramsay is buried here; in popular beliefs she was thought to have brought the plague to London.

London bridge is falling down

Falling down, falling down

London Bridge is falling down

My fair lady.

In 1973, Queen Elizabeth inaugurated the new bridge of the capital, designed by four engineers. Its structure is very simple and functional, without decorations. It is often used as an outdoor setting for film shooting. For example, in the film About a Boy, filmed in 2002 and starring Hugh Grant, the actor crosses the bridge during the rush hour, walking against the steady flow of employees heading for the City.

On 31st August 2008, instead, Amanda Cottrell, honorary citizen of the City, crossed the bridge with a sheep on a leash. She was not acting out the scene of a film, but doing it merely on a whim of her own, after having discovered that according to an old law from the Eleventh Century which had never been revoked, it was perfectly admissible.